Winnipeg, Manitoba / March 31, 1946

|

Six months after the murder of Arthur Badger, another taxi driver, Johann (Jo) Johnson, was killed in very similar circumstances. Once again the scene of the attack was a sparsely-populated suburban area, and once again the victim was savagely beaten with a blunt instrument. On Sunday morning, March 31, 1946, two bored soldiers awaiting discharge at Fort Osborne barracks decided to go for a walk in the freezing drizzle. As they passed a clearing in the bush along Kenaston Boulevard, about half a mile south of the barracks, one of them noticed Mr. Johnson's dark blue 1940 Chrysler stuck in the mud about 70 yards east of the road. On closer examination the two soldiers discovered the body of the taxi driver lying on the ground about 18 feet from the car. Mr. Johnson's skull was badly injured and marked by eight deep lacerations. His trouser pockets had been turned out, but a wallet containing $35 was still in his jacket. The coroner estimated the time of death as 3 or 4 a.m. The 43-year-old Mr. Johnson was a native of Iceland who came to Winnipeg in 1922. He had been an owner-operator with United Taxi since 1937. The evidence at the murder scene indicated that Mr. Johnson's killer or killers had dragged his body from the car and tried to drive away, but became stuck in the mud. Tire tracks showed that a second car or truck became stuck at about the same time and had been extricated with considerable difficulty. In the two weeks following the discovery of the murder, several pieces of evidence turned up. A woman's footprints were found about half a mile away from the body, and near the prints was a receipt for $79 made out to Jo Mr. Johnson for the care of his estranged wife in the Selkirk mental institution. Subsequently a second wallet, containing papers belonging to Mr. Johnson but no money, was picked up in the same area. The murder weapon, an 18-inch-long bridge construction bolt weighing nearly three pounds, was retrieved from a pool of water about 70 feet from the body. It was wrapped in several sheets of newspaper and tied with cord. A second set of footprints was discovered, apparently left by a woman running away from the murder scene and wearing only one shoe. Near these prints was a discarded handkerchief bearing the initial "J". Noting that the footprints seemed to head toward some distant dairy farms, the manager of Royal Dairies interviewed several farmers in the area and his efforts resulted in the identification of the shoeless woman. She was arrested as a material witness and spent the next month in jail under close questioning by Winnipeg police detectives, and it was her testimony that led to the arrest and conviction of a Winnipeg man for Jo Mr. Johnson's murder. In the meantime Jo Mr. Johnson's funeral became a public event. Ninety people packed the small funeral chapel and two hundred more stood outside. It was estimated that almost a third of Winnipeg's 300 licensed cabs took part in the procession. United Taxi shut its doors from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m. and the company's four-foot wreath was the centrepiece of many floral tributes. All the pall bearers were United drivers. Photos of the funeral appeared on the front page of the Winnipeg Tribune. The Greater Winnipeg Taxicab Association offered a reward of $500, later boosted to $750, for information leading to the conviction of Mr. Johnson's killer. Crimes against taxi drivers suddenly became big news. Some cabbies told reporters that they were refusing to work the night shift; others told of carrying wrenches and knives to protect themselves. There was a debate about the need to equip cabs with protective shields and a family of drivers installed a wire mesh screen behind the front seat of their cab after one of them was assaulted. Two serious incidents grabbed the headlines. Five days after Mr. Johnson's murder Moore's Taxi driver Sam Walsh had to flee from his cab when a young man threatened him with a revolver. Police quickly apprehended the culprit who openly boasted about his intention to shoot Walsh. Three days later a McMillan Taxi driver became suspicious of the three passengers in a United cab and followed it to its destination. The United driver, Donovon Clayton, had also anticipated a robbery attempt and jumped from his cab as the three men were on the point of attacking him. Clayton and the driver and passenger of the McMillan cab subdued one of the suspects and held him for police. However, interest in Mr. Johnson and other cabbies quickly waned with the arrest of the alleged murderer. An entirely new drama now began to unfold. On the night of Mr. Johnson's murder the suspect and the shoeless woman had attended a party at the woman's residence. During the party the woman drank heavily and quarreled with her husband before storming out of the house sometime before 3 a.m. The suspect left the party shortly afterward. According to the woman the suspect met her by prearrangement a short distance from the house and the two flagged down a taxi, intending to go back to the man's apartment. However, they quarreled on the way and the woman stopped the taxi, walking home from the point where her first set of footprints was found. Her description of the cab and driver did not tally with Mr. Johnson and his Chrysler. [Next column] |

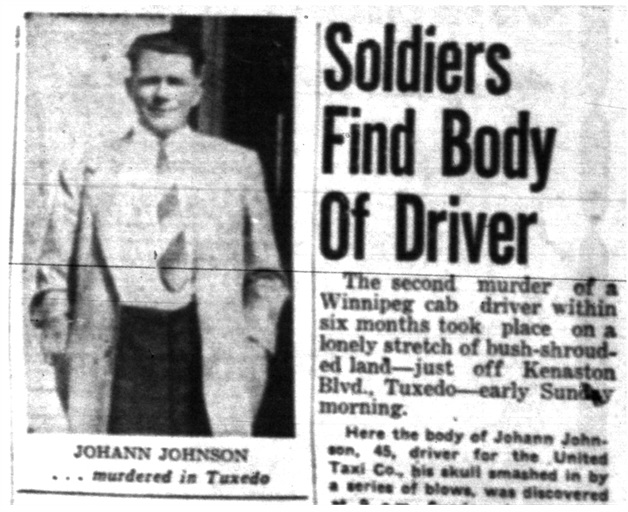

Johann Johnson. (Source: Winnipeg Tribune, April 1, 1946, p. 1) The woman subsequently made a whole series of increasingly elaborate and contradictory statements. In the statement that sealed the suspect's fate she claimed that he returned in the cab a few minutes after letting her off and when she approached the car she saw, first, the murder weapon on the floor; then the suspect with his left arm poised to strike the driver from behind; and finally, the driver lying across the front seat. At this point she fled the scene and lost one of her shoes. In later statements the woman claimed that the man in the back of the cab was not the suspect but a stranger wearing a hat. For his part, the suspect denied sharing a cab with the woman, claiming that he had hailed his own taxi and gone straight home from the party by himself. In the trial that followed the suspect was found guilty of murder primarily on the most incriminating version of the woman's story. His defence counsel took the case to the Manitoba Court of Appeal based on the judge's controversial charge to the jury. Four of the five justices denied the appeal, but a lone dissent allowed the case to be referred to the Supreme Court of Canada. The Supreme Court granted the appeal and ordered a new trial. At his second trial the suspect was once again convicted of murder. A second appeal was turned down unanimously by the Manitoba court, and the absence of a dissenting vote meant that no further appeal could be made to the Supreme Court. The only avenue now open was a request for clemency. During the two years that the suspect spent behind bars public opinion began to shift in his favour. He had no previous criminal record and apart from his war service -- he was wounded while serving with an armoured unit in Europe -- he had worked for ten years at Gray's Auction Rooms in Winnipeg. The Gray family was convinced of his innocence and footed the bill for his defence. The woman's credibility as a witness dwindled as she continued to change her testimony. Many people came to believe that the suspect was convicted on highly dubious evidence, and that the very apparent hostility of the judges in both trials had unduly influenced the juries to return guilty verdicts. A committee led by several lawyers and including some members of the Manitoba legislature gathered 10,000 names in support of clemency for the suspect. The woman, recanting her earlier statements, flew to Ottawa to appeal to the Minister of Justice on the suspect's behalf. Nevertheless the federal cabinet refused to intervene and he was hanged at Headingley Gaol on April 16, 1948. The story is detailed by William E. Morriss in his book Watch the Rope (Winnipeg: Watson Dwyer, 1996). Mr. Morriss was a Free Press reporter during the 1940's and 1950's and covered the trials of the last seven men to be executed in Manitoba. He makes a strong case for the suspect's innocence and his account of the judicial process that led to the execution makes depressing reading. The execution went off without a hitch and that may have been suspect's only good fortune in the final two years of his life. Two of Manitoba's last seven executions were horribly bungled, with one man strangling to death at the end of the rope and another being partially decapitated. Mr. Morriss is not the first to point out that Canada's executioners have a well-deserved reputation for incompetence. Hence the title of Mr. Morris's book. Assigned to his first execution at Headingley Gaol the green young reporter was cautioned by Sheriff Murray Kyle about being too quick to follow the attending physician down under the scaffold. "Don't close your eyes," advised Sheriff Kyle. "Watch the rope. If it begins to jiggle around, don't go downstairs, at least not for some time. If it snaps back, for God's sake don't go downstairs. You can get the details from someone else." |

• Driver Profiles

• Driver Profiles